Online Courses Look for a Business Model

Wall Street Journal

By MELISSA KORN And JENNIFER LEVITZ

January 1, 2013

Professor Jeremy Adelman has taught a world-history class at Princeton University for several years, but as he led about 60 students through 700 years of history on the ivy-covered campus this past fall, one thing was different: Another 89,000 students tuned into his lectures free of charge via Coursera, an online platform.

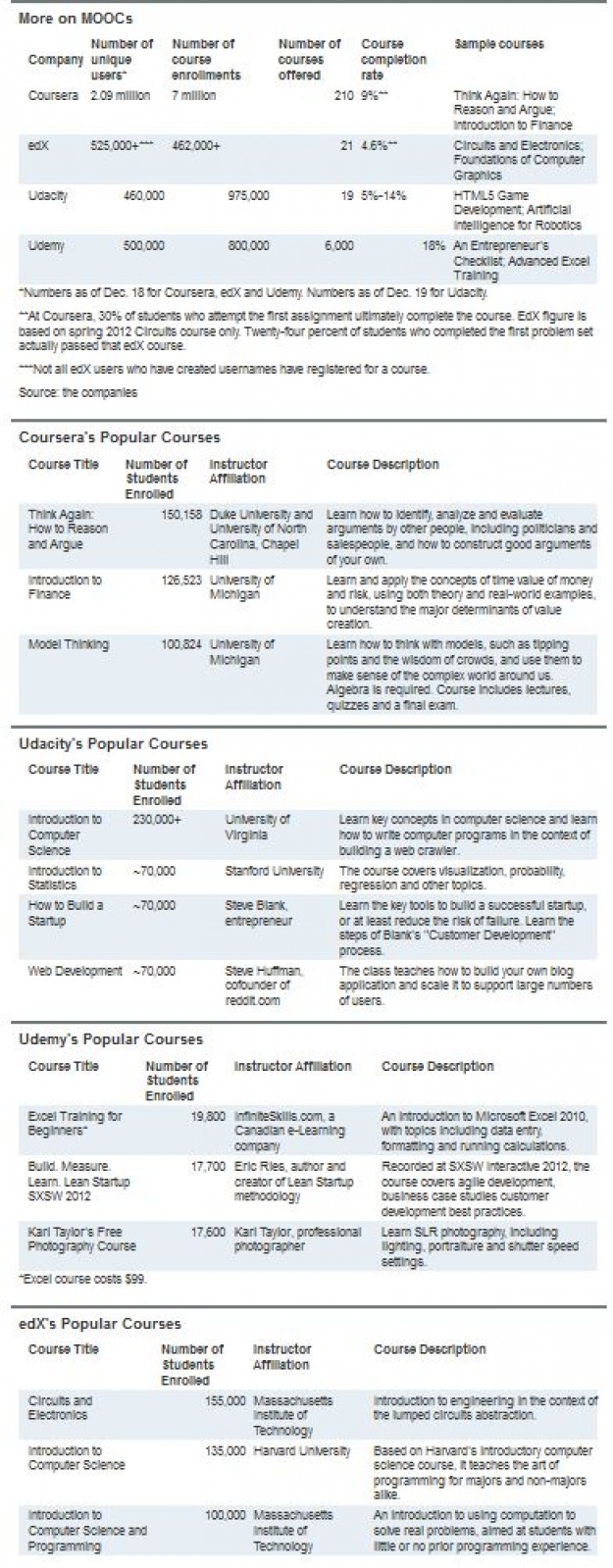

Those kinds of numbers, and their potential for remaking higher education, have generated plenty of excitement about massive open online courses—dubbed MOOCs. They've also lured venture investors and universities, who have put millions of dollars into companies like Udacity, Coursera and edX, which partner with schools or instructors to offer these courses.

The most popular of these classes enroll hundreds of thousands of students globally, and while they're taught by star instructors from top universities, they generally don't carry credit that can be applied to a college degree.

While backers say the short, digestible lessons are nothing short of revolutionary, MOOC providers are still figuring out how to keep basic course access free while generating revenue.

Sebastian Thrun, a Stanford University professor and co-founder of Udacity, which launched in 2012 with a $21.5 million bankroll from such prominent backers as Andreessen Horowitz, says his fledgling industry is in "a state of experimentation."

Some of the Partner Schools

Coursera: Princeton University, Duke University, Stanford University, University of Pennsylvania, Emory University, Mount Sinai School of Medicine

edX: Harvard University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, University of Texas system, University of California, Berkeley, Georgetown University

Udacity and others are trying out different business models, such as matching students with employers, licensing content to schools and charging for proctored exams, yet it's unclear what might stick—or, more importantly, can actually earn money.

"Nobody has any idea how it's going to work," says Dave Cormier, manager of Web communications and innovation at the University of Prince Edward Island, who was involved in earlier iterations of MOOCs a few years ago and has been credited with coining the term in 2008. "People have ideas of how to monetize it, but simply don't have any evidence."

Coursera, another firm with Stanford founders and $22 million in funding from Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers and others, recently began notifying students that they can opt in to a job-placement service, where recruiters can access details of their class performance. But the company matched only a handful of students in its months-long pilot and is still determining the fee structure.

While he declines to provide dollar figures, co-founder Andrew Ng acknowledges "it's still a business model that we're fleshing out."

MOOCs are "an innovation looking for a business model," says Kevin Kinser, an associate professor of higher education policy at the State University of New York at Albany. Online courses may be valuable supplements to regular classes, but Mr. Kinser, whose research focuses on nontraditional higher education models, says it's hard to see how they can be more than altruistic endeavors.

Venture investors seem undaunted. New Enterprise Associates Inc. put $8 million into Coursera just weeks after NEA general partner Scott Sandell learned that the company's founders were still debating whether to proceed as a nonprofit or for-profit venture.

"The business model was fairly unclear, but there were some plausible ideas about how Coursera could turn into a sizable company," Mr. Sandell says.

About 350 companies have signed up to access Udacity's job portal in recent months, though it has placed just about 20 students so far. Recruiters pay for successful matches, and Mr. Thrun says Udacity charges "significantly" less than Silicon Valley headhunters, whose cut he says can be two to three months of a candidate's starting salary.

Udacity earns additional money from courses created by talent-hungry technology companies including Google Inc. GOOG +1.77% and Autodesk Inc. ADSK +3.59% Mr. Thrun says that with money from job referrals and sponsored classes, "we will be able to survive quite well," though the company, like other course providers, declines to provide financial projections.

EdX, a nonprofit founded with $30 million each from Harvard University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology, is also letting companies use its platform to offer their own training courses.

With thousands of students in any one class, the varied quality of student work is a barrier to widespread acceptance of MOOCs. But proctored exams, which could help ensure academic rigor, may also offer a revenue opportunity.

Udacity and edX have both joined with Pearson PSON.LN +1.68% PLC's Pearson VUE to offer fee-based proctored exams at the company's 450 test centers world-wide. Udacity charges $89, while edX's president, Anant Agarwal, expects his to be under $100 when the first exam is announced soon. Coursera is considering similar plans.

With completion rates for most MOOCs usually falling below 10%, the earning potential is limited. If 10,000 people take a course, and 1,000 finish, early trials suggest just a fraction of those students are likely to pay for verified exams. At $89 a head, a successful course might net just a few thousand dollars in proctor fees.

Content licensing is showing some promise, with schools signing on to use MOOCs for large survey courses, which they'll complement with in-person discussion groups and supplemental assignments. Antioch University, which enrolls about 5,000 students over five U.S. campuses, announced in October that it would allow students to take some Coursera classes for credit.

Neither side disclosed the terms of the deal, though Mr. Ng says Coursera received a "modest" fee and is in similar talks with other schools.

Several school administrators admit they're teaming up with course providers mainly because they fear missing out on something big. So far none of the elite schools that provide content for companies like Coursera and edX offer credit for those classes, though attitudes may be shifting.

The American Council on Education, an influential association of university presidents, is considering for-credit status for some Coursera courses. And some schools are designing their own for-credit offerings, creating potential competition for Coursera and its peers. In November 10 colleges, including Duke University, joined forces with another company to launch a series of credit-bearing courses for students at those schools.

Venture funders are optimistic the math will work out eventually. Andreessen Horowitz partner Peter Levine, a Udacity board member, acknowledges that revenue plans are hazy right now, but says he expects "some real direction" on business plans within the year.

At least some providers of MOOCs may decide that nonprofit status is the way to go, taking cues from Carnegie Mellon University's decade-old Open Learning Initiative, which has nearly 45,000 students enrolled across its free and fee-based classes. While it relies mainly on grant funding and offers classes free to independent learners, it has begun charging $15 to $25 per student for the academic versions of some courses—used at schools such as University of California, Berkeley—to ensure the initiative could sustain itself.

Candace Thille, the project's director, says the new course providers have a lot to learn, especially because they'll have to answer to investors. "You can't just cross your fingers and hope money flows in at some point."